LEAGUE INTERVIEW with R.M. Romero

Pop-Up Questions, a Cell Photo Story, and Interview

PREORDER here

R. M. Romero (she/they) is a Jewish Latina and international bestselling author of fairy tales for children and adults. She lives in Miami Beach with her cat, Robin Goodfellow, and spends her summers helping to maintain Jewish cemeteries in Europe.

POP-UP QUESTIONS

What writer romanized being a writer for you as a young person?

Brian Jacques, the author of the Redwall series. I went to a book signing of his when I was eleven. Jacques was a gregarious man and extremely generous with all his young readers. Listening to him talk made me realize that telling stories was a real job that living, breathing people had, and I became determined to one day have that job myself.

What is a quote that has endured in your mind?

“All stories are about wolves. All worth repeating, that is. Anything else is sentimental drivel.” Margaret Atwood was, in my opinion, entirely correct.

How has technology been a part of your writing?

Because I travel so often, I’ve written several books almost entirely on my phone. It’s nice to have an entire story at my fingertips like that.

What music do you love on road trips?

Bubblegum pop songs. The more of an earworm they are, the better.

What is your favorite bit of writer lore or (not harmful) gossip?

Once upon a time in Berlin, Franz Kafka met a little girl who had lost her doll. To console her, Kafka told the girl that her doll wasn’t actually lost; she was traveling the world and would eventually return. Over the next few weeks, he wrote to the girl as the doll, describing all the fantastic places she was visiting. Finally, Kafka purchased a doll and gave it to the girl, who was initially confused. This doll didn’t look like her doll at all! But then Kafka presented the girl with the doll’s final letter, which said: “My travels have changed me.” Years later, long after Kafka had died, the girl found a note inside the doll signed by him. “Everything you love will probably be lost, but in the end, love will return in another way.”

CELL PHOTO STORY

I took this picture of myself in a mirror when I was in Lviv, Ukraine in 2018. I went out for a walk one rainy morning and stumbled across a courtyard that was full of abandoned toys. I don’t know why those toys were there; I don’t think I want to, either. The mystery makes them more interesting.

THE INTERVIEW

NOTE: I sent the interview questions to R.M., and Ever was looking over my shoulder. When she saw the author, she gasped! People gasp outside books! She said, “Oh my god mom, that’s who wrote The Dollmaker of Krakow. That’s like one of my favorite books. They’re famous!” I thought it was MARVELOUS that a kid can still think of any writer as being famous, and more marvelous that Ever loves R.M.’s work so much. So this first question was from Ever, and the rest are from me. Obviously Ever has been thinking a lot about the Jewish experience in America, and this was on her mind. Enjoy. -Maggie

Growing up Jewish, how did other kids who weren't Jewish respond to that? In my school I never hear anyone hating on Jewish people or saying anything negative, so I'm wondering if it was different when you were a kid?

I actually didn’t grow up Jewish! I converted to Judaism when I was in my twenties. But I know a lot of Jews my age and their experiences as kids varied. For some of them, their biggest frustration when it came to being Jewish was having to sing Christmas carols at school or needing to explain to their teachers that Yom Kippur was a real holiday and should count as an excused absence. Others had pennies thrown at them, were told that they had killed Jesus, or asked if they had horns. How my Jewish friends were treated by their peers seemed to depend largely on the community they grew up in. Did that community value diversity, or did the people in it see diversity as a threat?

I'd like to begin by thanking you for agreeing to do this interview series of writers who are openly Pro-Palestine. How has your experience of being Jewish influenced your desire for a free Palestine and peace between Israel and Palestine?

As a Jew who does field work in Poland related to the Holocaust, I’m hyper aware of what happens when we treat the lives of other human beings as lesser than our own. So “Never again” must mean “Never again for anyone.”

Has expressing your support for Palestine on social media had any direct effects on your writing career or personal life?

Becoming more educated about Palestine and being vocal about my views online has impacted many aspects of my life. Rifts have developed between me and people who don’t feel the same way I do; some (now former) fans have gotten upset that I’ve publicly called for a ceasefire. On the other hand, I’ve connected with many like-minded authors, book bloggers, and publishing professionals, particularly other Jews who also support Palestine.

Why do you think it's important for writers to speak out?

I’m going to default to the old Spiderman cliche: “With great power comes great responsibility.” And as writers, our power is in our words. I personally have written numerous anti-genocide books, from The Dollmaker of Krakow to The Ghosts of Rose Hill to more recently addressing Russia’s ongoing genocide against Ukranians in Death’s Country. I chose to write those stories because I feel strongly about that kind of violence and want more people, particularly young people, to be aware of it. And I choose to speak out for the same reason. I think that for kidlit authors especially, it’s imperative that we say all children and their families deserve to live in peace and that includes Palestinian children and their families.

Is there any writing or text that has been particularly important to you when forming your ideas on Israel and Palestine?

I Saw Ramallah by Palestinian writer and poet Mourid Barghouti was such a lyrically written yet intensely tragic book. It showed the impact that the occupation of the West Bank has had on the lives and culture of Palestinians in a very personal way. And, while not a book, the documentary “Born in Gaza” opened my eyes to the deprivation and violence Palestinian children have been subjected to for years.

Your novel, Death's Country, is an incredible fantasy world where a teenage boy who drowns, bargains for his life back, and then has to visit death's country again to help his lover reunite with her body. The themes of polyamory, queerness, family, and facing our shadow selves are thrilling. How did the seed for this novel get planted?

I’ve always been fascinated by the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. I was frustrated by the tragedy of it, but I found the rest of it so compelling. Orpheus wasn’t a typical hero; he was neither a great warrior nor a clever trickster. He was just a man who descended into the darkest place in the cosmos with nothing but a song in order to rescue the person he loved.

Shades of Orpheus have always appeared in my work because of that interest in the myth, but I finally decided to try my hand at my own retelling in 2022. I knew I wanted to write a story about love conquering all and I wanted my protagonists to be teens who represent where I live in Miami. They would be Latine and queer and obsessed with music and art. They would engage in the same kinds of magic that I practice.

The City of the Dead, where my heroes travel, had its origins in my teenage years. I was trying to imagine what the afterlife might look like and what came to mind wasn’t clouds and angels and harps. It was a city, where it always rained and the dead couldn’t quite let go of their old lives. When I told some people about it, they assumed it was Hell; I thought it was more of a haunting.

Endings often plague authors- how did the writing of the ending of Death's Country go?

I’m an author who struggles with beginnings. It usually takes me multiple different tries to find the best way into the story! But one of the first things I know about a book is how it’s going to end.

Classic works and themes of literature are important in Death's Country. How did that come about?

I was a bookworm who read Dante and Homer when I was twelve, and I was intrigued by the format of those stories. Here were these epic fantasies that were written as poems and, in the case of The Iliad and the Odyssey, were not just recited orally but made into songs. Because music is such a key part of Death’s Country and the Orpheus myth, I thought about how to make the book sound like a song. I also wanted to include literary references teens would probably get, since a lot of the classic literature that I read in middle and high school is still required reading today. (For better or for worse.)

Novelists often have first readers before the final submission of the book. Do you ever have teenagers read your work before submission?

I haven’t, but I would love to in the future! I think it’s a fantastic idea to get the target audience’s opinions about what works in a story and what doesn’t. I remember being a teenager and the emotional experiences I went through very clearly, but times have changed when it comes to day-to-day life.

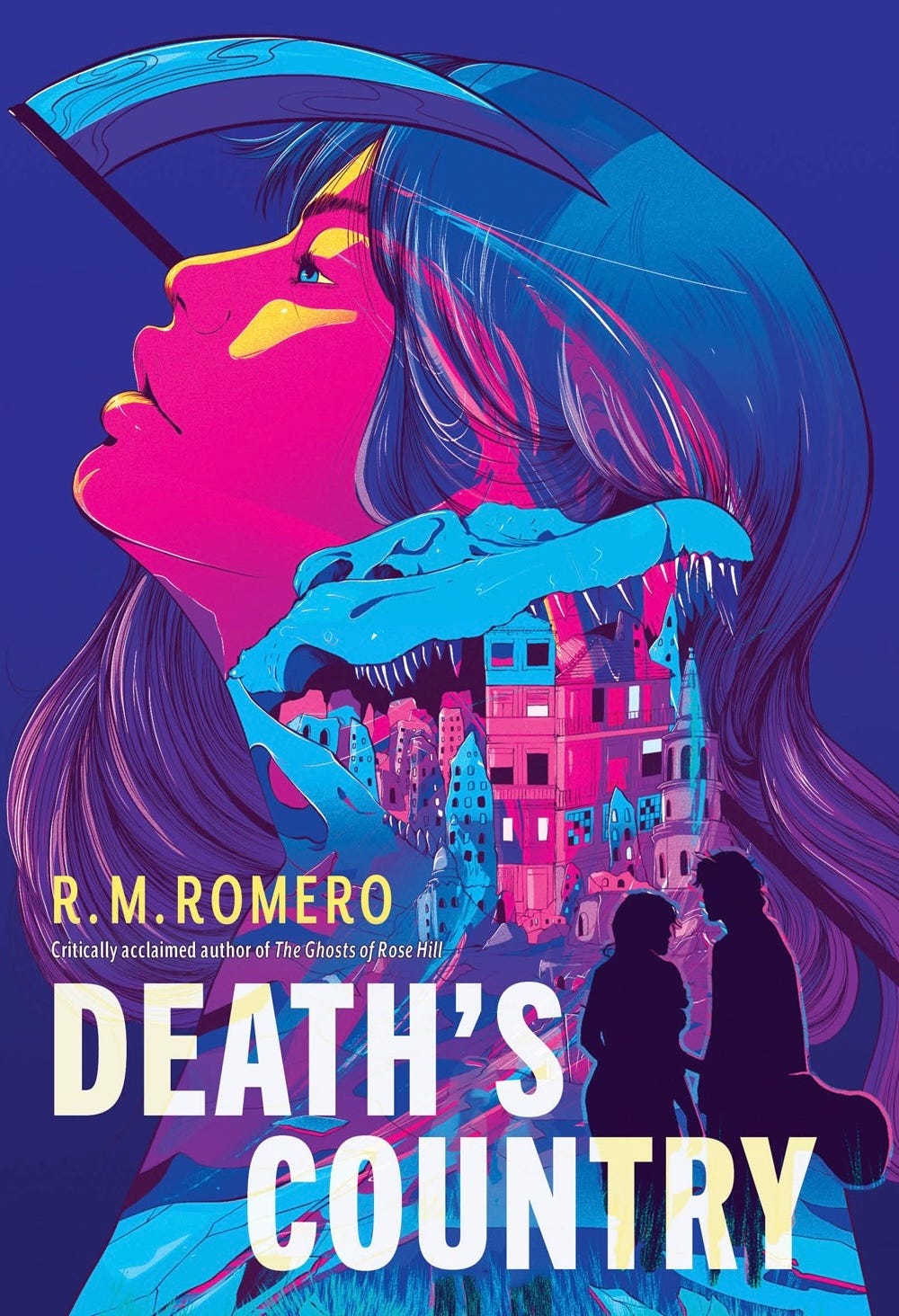

The cover of Death's Country is amazing! I love it. Did you have a hand in choosing the artist?

I did! I had created a Pinterest board of pictures that captured the mood of the book, which then I sent to my publisher. I have a background in visual art, so I generally have a clear idea of the aesthetic I’d like a cover to have. My publisher then gave me a choice of three different artists who they felt would be a good fit.

What was your writing life like while writing this book, in the most prosaic way- any routines, lucky charms, music you have to listen to?

I tend to write late at night when the world is quiet and I need background music to write. Music puts me in the right headspace to connect with my characters and follow along with the flow of the melody. Death’s Country required a lot of David Bowie, Hozier, and covers of classic rock. Here is my playlist if anyone is interested!